NiNo: Learning to Accelerate Training of Neural Networks

Explaining our ICLR 2025 paper and visualizing neuron permutation symmetry.

Training large neural networks is famously slow and expensive. In our paper, Accelerating Training with Neuron Interaction and Nowcasting Networks, presented at ICLR 2025 in Singapore, we introduced a new way to speed things up. We treat a neural network as a graph of interacting neurons, or neural graph

From Adam to NiNo

Due to massive training costs, recent years have seen a surge of faster adaptive optimizers: Shampoo

NiNo is a GNN-based model that takes a history of past parameter values along the optimization trajectory (obtained with Adam or another optimizer) and makes a jump by predicting future parameter values. After making the prediction, optimization is continued with Adam, then followed by NiNo’s another prediction and so on.

This periodic nowcasting idea is borrowed from Weight Nowcaster Network (WNN)

{

"data": [

{

"type": "scatter",

"name": "Adam",

"x": [

645.4,

1098.0,

1559.6,

2021.3,

2482.9,

2944.5,

3406.2,

3472.6,

3867.8,

4329.4,

4791.1,

5252.7,

5714.3,

6176.0,

6637.6,

6769.6,

7099.3,

7560.9,

8022.5,

8484.2,

8945.8,

9407.4,

9869.1,

10066.6,

10330.7,

10792.3,

11254.0,

11715.6,

12177.2,

12638.9,

13100.5,

13363.6

],

"y": [

1290.42,

654.89,

491.01,

415.95,

367.21,

333.12,

306.04,

302.24,

282.43,

264.16,

246.73,

233.03,

221.53,

211.24,

202.02,

199.9,

194.86,

187.62,

181.82,

176.28,

171.77,

167.21,

163.92,

162.06,

160.25,

157.63,

153.97,

151.23,

149.08,

146.99,

144.91,

144.02

],

"mode": "lines",

"line": {

"color": "#1f77b4",

"width": 2.5

}

},

{

"type": "scatter",

"name": "WNN (Jang et al., 2023)",

"x": [

654.8,

1098.0,

1559.6,

2021.3,

2482.9,

2944.5,

3406.2,

3472.6,

3867.8,

4329.4,

4791.1,

5252.7,

5714.3,

6176.0,

6637.6,

6769.6,

7099.3,

7560.9,

8022.5,

8484.2,

8945.8,

9407.4,

9869.1,

10066.6,

10330.7,

10792.3,

11254.0,

11715.6,

12177.2,

12638.9,

13100.5,

13363.6

],

"y": [

1290.42,

653.73,

444.74,

387.85,

326.93,

303.61,

266.84,

264.77,

251.27,

227.12,

216.34,

199.39,

192.44,

180.71,

175.41,

170.13,

167.42,

163.54,

157.7,

154.93,

150.43,

148.24,

144.45,

143.78,

143.02,

140.42,

138.9,

136.51,

135.4,

133.53,

132.68,

131.58

],

"mode": "lines",

"line": {

"color": "#2ca02c",

"width": 3,

"dash": "dash"

}

},

{

"type": "scatter",

"name": "NiNo (ours)",

"x": [

648.7,

1098.0,

1559.6,

2021.3,

2482.9,

2944.5,

3406.2,

3472.6,

3867.8,

4329.4,

4791.1,

5252.7,

5714.3,

6176.0,

6637.6,

6769.6,

7099.3,

7560.9,

8022.5,

8484.2,

8945.8,

9407.4,

9869.1,

10066.6,

10330.7,

10792.3,

11254.0,

11715.6,

12177.2,

12638.9,

13100.5,

13363.6

],

"y": [

1290.42,

652.54,

425.26,

371.58,

294.78,

271.73,

231.12,

228.8,

217.43,

193.29,

184.29,

169.48,

163.7,

154.62,

150.46,

149.22,

144.61,

141.77,

138.42,

136.37,

134.1,

132.88,

131.09,

130.71,

130.05,

128.99,

128.08,

127.1,

126.53,

125.55,

124.76,

124.48

],

"mode": "lines",

"line": {

"color": "#D44841",

"width": 5

}

},

{

"type": "scatter",

"name": "target perplexity",

"x": [

636.4,

13363.6

],

"y": [

147.0,

147.0

],

"mode": "lines",

"line": {

"color": "#7f7f7f",

"width": 2,

"dash": "dot"

}

}

],

"layout": {

"title": {

"text": "NiNo achieves ~2× speedup compared to Adam.",

"font": {

"size": 20

}

},

"xaxis": {

"title": "training iteration",

"range": [

0,

14000

],

"tickvals": [

0,

2000,

4000,

6000,

8000,

10000,

12000,

14000

]

},

"yaxis": {

"title": "validation perplexity",

"type": "log",

"range": [

2,

3

],

"tickvals": [

100,

200,

300,

400,

600,

1000

],

"ticktext": [

"10\u00b2",

"2\u00d710\u00b2",

"3\u00d710\u00b2",

"4\u00d710\u00b2",

"6\u00d710\u00b2",

"10\u00b3"

]

},

"legend": {

"x": 1.0,

"y": 1.0,

"xanchor": "right",

"yanchor": "top"

},

"margin": {

"l": 70,

"r": 20,

"t": 60,

"b": 60

},

"annotations": [

{

"x": 300,

"xref": "x",

"y": 0.60,

"yref": "paper",

"text": "Nowcast",

"showarrow": false,

"textangle": -45,

"font": {

"size": 10

},

"xanchor": "left",

"yanchor": "bottom"

},

{

"x": 1300,

"xref": "x",

"y": 0.40,

"yref": "paper",

"text": "Nowcast",

"showarrow": false,

"textangle": -45,

"font": {

"size": 10

},

"xanchor": "left",

"yanchor": "bottom"

},

{

"x": 10300,

"xref": "x",

"y": -0.03,

"yref": "paper",

"text": "Nowcast",

"showarrow": false,

"textangle": -45,

"font": {

"size": 10

},

"xanchor": "left",

"yanchor": "bottom"

}

]

}

}

The figure shows the results of Adam without and with nowcasting using our NiNo. “Nowcast” steps are shown at step 1000, 2000 and 11,000 for visualization purposes, but this step is applied every 1000 steps in our experiments. Note the ~2× reduction of the number of steps required by NiNo to achieve the same validation perplexity as by Adam. The optimization task in this example is autoregressive next-token prediction on the WikiText103 dataset that NiNo has not seen during its training.

NiNo Details

As NiNo is a neural network (namely, a GNN), it needs to be trained first before we can use it to speed up optimization. To do so, we collected and publicly released a 🤗dataset of checkpoints with optimization trajectories on 2 vision and 2 language tasks. Even though collecting these checkpoints and training NiNo is computationally expensive, this one-time cost is amortized, meaning the same trained NiNo can potentially be used across many tasks, ultimately reducing total training cost.

Neuron Permutation Symmetry

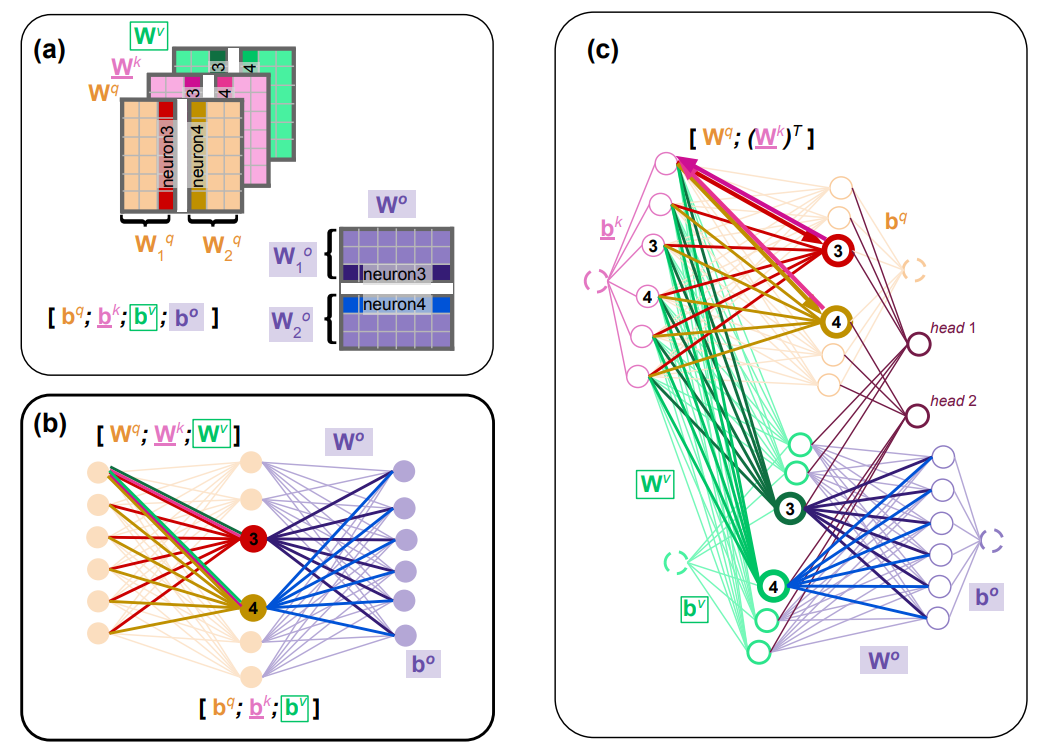

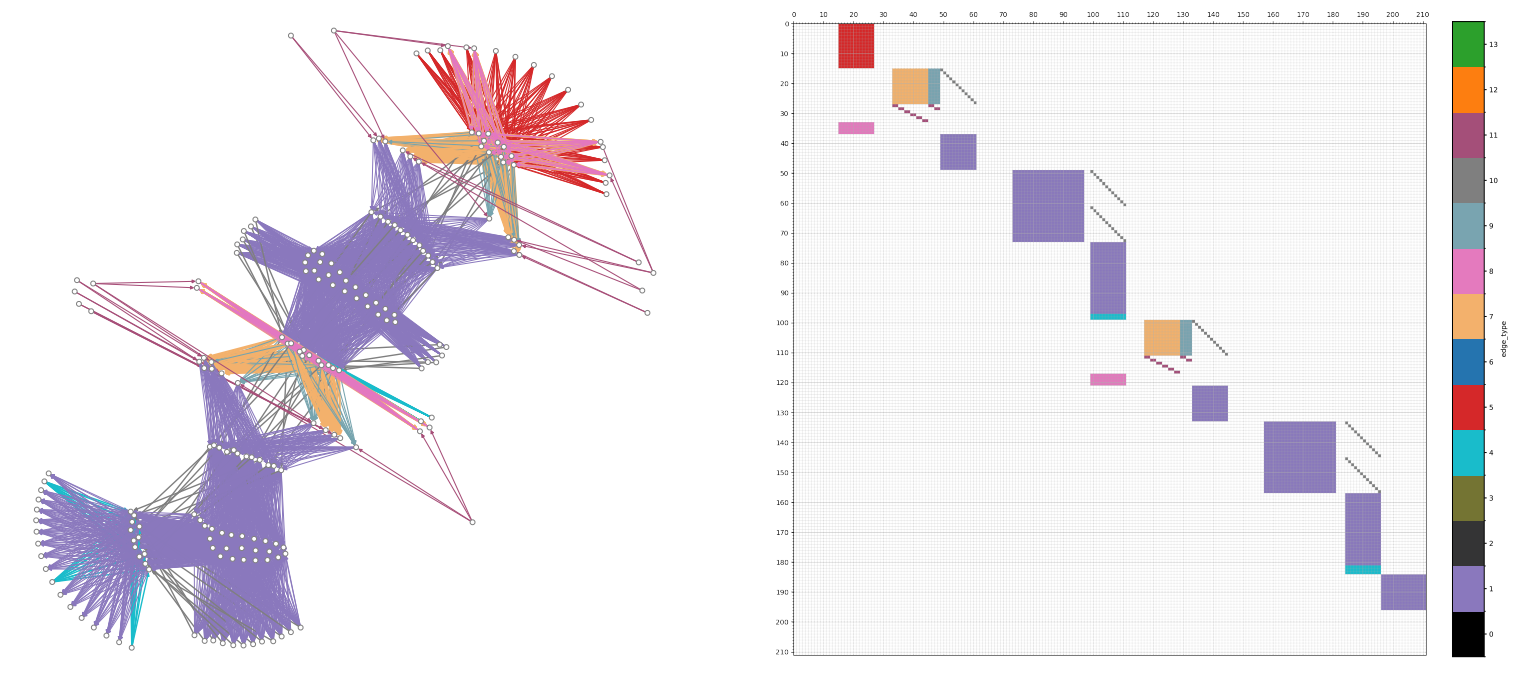

Developing a strong parameter nowcasting model requires many specific design choices and, perhaps most critically, accurate modeling of neuron permutation symmetry

We can permute the neurons in the hidden layer by applying a permutation matrix \(\mathbf{P}\) to the weights in layer 1 (permuting rows) and the inverse permutation to the weights in layer 2 (permuting columns), resulting in:

\[f(\mathbf{x}) = (\mathbf{W}_2 \ P^{-1}) \ \sigma(P \ \mathbf{W}_1 \ \mathbf{x}).\]Given the orthogonality property of permutation matrices, \(\mathbf{P}^{-1} = \mathbf{P}^T\), and that the activation function σ is element-wise, we can see that the output of the network remains unchanged:

\[f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_2 \ \mathbf{P}^{-1} \ \sigma ( \mathbf{P} \ \mathbf{W}_1 \ \mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_2 \ \mathbf{P}^{-1} \mathbf{P} \ \sigma (\mathbf{W}_1 \ \mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{W}_2 \ \sigma(\mathbf{W}_1 \ \mathbf{x}).\]Let me now visualize this symmetry using a simple demo, where the output is dynamically computed given the current order of neurons for some fixed input. You can click the “Swap Random Pair” button to randomly swap two (just for simplicity) hidden neurons and see how the network diagram and weight matrices change, while the computed output should (hopefully!) remain the same. You can also toggle the “Correct Permutation” option off to turn off the permutation of the weights in the second layer, in which case the output changes. You can reset the demo to the original state by clicking the “Reset” button.

💡 Watch how swapping two hidden neurons changes the network diagram and weight matrices, but the output stays the same!

Neuron Permutation Symmetry in Transformers

To make NiNo work well for LLMs and Transformers in general, it was critical to carefully construct the neural graph for multi-head self-attention, making it stand out compared to WNN (which ignores the neural network structure). This is a tricky part as the illustration below shows, but we implemented it for many different Transformer layers.

Visualizing the permutation symmetry in Transformers using a demo is also possible, but I leave it for future work (or please submit a PR to this blog post).

Results that Stand Out

- NiNo achieves roughly a 2× speedup compared to Adam, which is rarely achieved by manually designed optimizers in practice

Which are considered remarkable if a 1.2–1.3× speedup is achieved. . - NiNo speeds up optimization across 9 vision and language tasks that we systematically evaluated, achieving the same validation performance (accuracy or perplexity) as Adam in about half the steps on average across these tasks (see Table 2 in the paper).

- NiNo continues to speed up training for larger models beyond our main 9 tasks that are much larger than the models in the training checkpoints used to train NiNo (see Table 4 in the paper).

In addition, as shown below, applying NiNo is straightforward:

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM

from optim import NiNo

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_config(...) # some model

# NiNo is implemented as a wrapper around the base optimizer

# any optimizer other than Adam should also be possible to use with NiNo

opt = NiNo(base_opt=torch.optim.AdamW(model.parameters(),

lr=1e-3,

weight_decay=1e-2),

ckpt='checkpoints/nino.pt',

subgraph=False, # can be set to True for larger models (see Llama 3.2 example below)

edge_sample_ratio=0, # can be set to a small positive number for larger models (see Llama 3.2 example below)

model=model,

period=1000,

max_train_steps=10000)

for step in range(10000):

if opt.need_grads: # True/False based on the step number and period

opt.zero_grad() # zero out gradients

data, targets = ... # get some batch of data

# base optimizer step (majority of the time)

outputs = model(data) # forward pass

loss = F.cross_entropy(outputs, targets) # compute some loss

loss.backward() # only compute gradients for the base optimizer

opt.step() # base_opt step or nowcast params every 1000 steps using NiNo

Learning to Optimize, Revisited

Our work connects to the broader “learning to optimize” literature, such as VeLO

Conclusion

Even though NiNo shows great speedups, it requires further work, for example:

- Making NiNo’s step more scalable (especially memory-efficient) to larger models - currently the message passing step in its GNN is a bottleneck;

- Improving speedups on larger tasks - for tasks with >1B parameter models we currently observe no speedup;

- Adding automatic ways to construct neural graphs and verify their correctness;

- Combining NiNo with learned optimizers to get the merits of both;

- Showing theoretical guarantees for convergence.

We have open-sourced our code and pretrained NiNo checkpoints at github.com/SamsungSAILMontreal/nino under MIT License and welcome contributions.

License

Diagrams and text are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY 4.0, unless noted otherwise.

Citation

@inproceedings{knyazev2024accelerating,

title={Accelerating Training with Neuron Interaction and Nowcasting Networks},

author={Boris Knyazev and Abhinav Moudgil and Guillaume Lajoie and Eugene Belilovsky and Simon Lacoste-Julien},

booktitle={International Conference on Learning Representations},

year={2025},

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: